THE SIREN SANG

"There's an understanding in Canada that

immigration is a net-positive for our society, and that we should continue to

have a very robust immigration system that welcomes those in need of protection

but also those that want to come and give us their skills and talents."

- Canadian Minister of Immigration Ahmed Hussen

Halifax’s history as a major east coast seaport is striking.

Halifax-based ships undertook the grim task of searching for bodies of the

victims of the sinking of the Titanic.

While some of the bodies recovered had to be buried at sea, a couple

hundred of them were brought to Halifax, where many were buried in three cemeteries

around the city.

But some five years later, an even more horrific, but for

some reason less known (at least in the U.S.), event occurred. A French cargo ship

carrying explosives for WWI from New York to Bordeaux via Halifax, collided

with another ship and caught fire in the harbor. It drifted into the pier and

exploded, destroying almost all buildings within a half-mile radius. Further

damage ensued from a resulting pressure wave and tsunami, wiping out an entire

section of the city and a community of first nation inhabitants. In the end,

some 2,000 people were killed and 9,000 were injured.

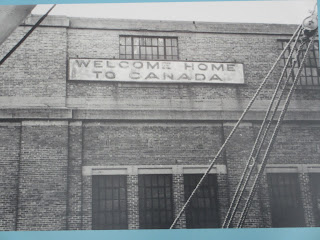

Throughout the middle of the twentieth century, Halifax

served as the major port of arrival for immigrants from Europe. The most active

period was between 1947 and 1971, when war survivors, war brides, and refugees

from Eastern Europe passed through the immigration portal at Halifax’s Pier 21.

An immigration museum now fills the halls that once housed the immigration

processing and detention center at Halifax. Those who know me know that I would

not be able to resist the siren song of an immigration museum.

Much like the U.S.’s Ellis Island, the Pier 21 Immigration

Museum explains the history of immigration to Canada. It does not gloss over

the darker elements of Canadian immigration policies—the 1939 turning away of

the MS St. Louis (just like the U.S., leaving its 900 Jewish passengers to

return to Europe and their deaths), the overtly racist policies, the subtler

racist policies, and the discretion that was sometimes exercised in abusive ways.

Interestingly, it also treats the history of relations between indigenous people

and European newcomers as an element of immigration history. But it also

showcases the opportunities and freedoms many migrants found, as well as their

contributions and challenges. One of the featured immigrants came from the U.S.

in the 1960s in order to avoid the Vietnam War.

It was a rainy day in Halifax, so my afternoon excursion—sailing

on a classic tall ship—was cancelled. But the day was enjoyable nonetheless.

The previous day was spent in Bar Harbor, Maine, where Beth

and I spent the morning strolling around town and the afternoon eating our way

through town on a “Tastes of Bar Harbor” tour. All foods were sourced and

prepared locally: lobster roll (perhaps the best I’ve ever eaten), wild

blueberry cake, maple and blueberry popcorn, French fries using local potatoes

(a major crop of Maine—who knew?) and fried in duck fat, and a locally-brewed

beer.

Yes, we rolled back to the ship.

Comments

Post a Comment